Sarah Sundin, @sarahsundin

What do ballet and writing have in common? We could all point to the junction of creativity and hard work, and to the great difficulty of “making it” in a competitive field.

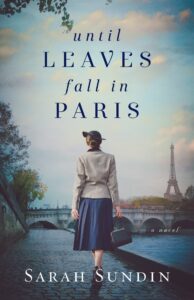

My latest novel, Until Leaves Fall in Paris, features an American ballerina at the Paris Opéra Ballet who ends up running a bookstore—and aiding the French resistance in World War II.

As a girl, I studied ballet all the way through high school at Lucille McClure’s School of Ballet in Whittier, California. Writing this novel brought back fond memories, not just of dancing, but of Miss McClure’s wisdom. She didn’t just teach ballet—she taught lessons for life. Many of which apply to writing.

Barre Work before Dancing

I didn’t take ballet lessons so I could do endless pliés and tendus at the barre. Boring! Why couldn’t we just dance?

We writers do a lot of whining too, don’t we? Why do I have to do social media, interviews, editing—whatever it is you don’t like? Why can’t I just write?

Every job under the sun has aspects we love and aspects that are pure drudgery. Writing is no different. Just as barre exercises train the dancer and teach discipline, writers’ “other” work trains us and disciplines us, builds our platform, and connects us with current and future readers. All vital.

Four Years to Pointe Shoes

Miss McClure was what we’d call “old school.” Things had to be done just so. One of her inviolable rules was that girls needed to be ten years old before going on pointe—and had to take at least four years of ballet and pass our first two Cecchetti examinations. We had to earn those shoes.

We writers dream of our books on the shelves—but it can take years. We need to learn the craft and the industry, and we have to pass our “examinations” by writing at a level that pleases agents and editors. Sometimes that takes four years. Sometimes far longer. But it’s an important part of the process.

If You Miss Practice…

When we grumbled about our exercises, Miss McClure would say, “If you miss one day of practice, you know it. If you miss two days, your teacher knows it. And if you miss three days”—and she would pierce us with her all-seeing gaze—“the audience knows it.”

Writing, like ballet, requires practice and discipline. Although I’m not an adherent to the “write every day” rule, to grow as writers does require regularity and time. Even before publication, keeping office hours—even if it’s half an hour three times a week—is an excellent habit to establish.

No Lamb’s Wool

Pointe shoes hurt. Another of Miss McClure’s old school rules banned us from stuffing the toes of our pointe shoes with lamb’s wool. She wanted us to feel the floor. Oh boy did we. The knuckles of my toes were covered with blisters and sores. But over time, calluses developed. Then we could dance with less pain while still feeling the floor.

Writing hurts. Critiques, contests, rejection letters, reviews—all cause blisters on our little hearts. But we can let calluses form, calluses that protect our hearts without letting us lose the “feeling the floor” sensitivity that makes us good novelists. So don’t use lamb’s wool. Put your work out for critique and enter it in contests. Let calluses form that allow you to handle the negative reviews later on.

Your Other Left Foot…

At least once in every class, one of the girls (often me) would begin an exercise with the right foot when we were supposed to start with the left. Miss McClure would smile and say, “Sarah—your other left foot.” That always made us chuckle, and then we’d correct ourselves.

Be kind to yourself. Don’t take yourself too seriously. Be quick to laugh at yourself. The writing industry can be brutal, and we writers can be tender souls.

There are many other pearls of wisdom from Miss McClure, and I was able to work some of her memorable lines into Until Leaves Fall in Paris. She was a woman of elegant grace who could silence a room of giggling girls with a single glare. And she taught me well.

Are there other areas of your life that have taught you important lessons for the writing life? What are they?

When the Nazis march toward Paris, American ballerina Lucie Girard buys her favorite English-language bookstore to allow the Jewish owners to escape. The Germans make it difficult for her to keep Green Leaf Books afloat. And she must keep the store open if she is to continue aiding the resistance by passing secret messages between the pages of her books.

Widower Paul Aubrey wants nothing more than to return to the States with his little girl, but the US Army convinces him to keep his factory running and obtain military information from his German customers. As the war rages on, Paul offers his own resistance by sabotaging his product and hiding British airmen in his factory. But in order to carry out his mission, he must appear to support the occupation—which does not win him any sympathy when he meets Lucie in the bookstore.

In a world turned upside down, will love or duty prevail?

Sarah Sundin is an ECPA- and CBA-bestselling author of World War II novels, including Until Leaves Fall in Paris. Her novels When Twilight Breaks and The Land Beneath Us were Christy Award finalists, The Sky Above Us won the 2020 Carol Award, and When Tides Turn and Through Waters Deep were named to Booklist’s “101 Best Romance Novels of the Last 10 Years.” A mother of three adult children, Sarah lives in California and enjoys speaking for church, community, and writers’ groups. She serves as Co-Director for the West Coast Christian Writers Conference. You can find her at http://www.sarahsundin.com