by Rachel Hauck, @RachelHauck

I’ve written a lot about dialog over the years but it’s a topic worth repeating. Dialog. Is. Key.

Talking is how we learn about people. The words they use, the tone of his or her voice, as well as interpreting someone’s body language, is how we form our opinion of people.

As authors, we have to resist the tendency to speak for our characters. Even in “deep point of view” where the reader is in the skin of the character, we have to let them do the talking.

Here’s an example. I’m in fast, first draft mode for my next book and my heroine described herself in prose.

She was reserved, quiet, self-deprecating.

As I was writing, I knew the line was wrong. Had that little hitch, you know, where you want to hit the backspace key.

But in fast draft mode, the goal is to keep going forward, discovering the story and not pausing to rewrite or edit.

Nevertheless, I called Susie May and read her the line. “I’m telling, aren’t I? I should put this in dialog.”

Yep. She agreed.

Luckily for me, there was another character on the page for my heroine to talk with. In fact, she’d been talking to him three lines previous.

I rewrote the line of prose with dialog.

Zane was driven, selfish, arrogant and rather emotionally detached.

“Maybe we could make one of those pacts,” he said.

“Like if we’re fifty and no one wants us?” What a depressing thought.

“Yea, but not fifty. Forty?”

“I’m only thirty, Zane. You’ll be forty in two years.”

“If you don’t want to, Prescott, just say so.”

“All right. Zane, you could never settle for a girl like me. I’m, I’m, I don’t know . . . the one who likes to hide in corners and stay in all weekend watching old movies or reruns of Frasier. I was the unpopular one in school. Somewhere beneath this skin and tight gown is a fat chick. No, I’m not your type.”

See where I’m going? Instead of telling the reader, I showed them. That’s really the essence of Show vs. Tell. Dialog.

Dialog reveals deeper aspects of the character. It also allows the reader to make his or her own assumption about the people on the page.

One of the beauties of story is the reader can insert herself into the page and relate to the characters how they see fit.

Tell the story between the quotes.

I was in writers meeting one time and one of the members read a chapter out loud to us for praise and critique.

I noticed that the best lines and descriptions were outside the quotes. The dialog went something like:

“Hello,” Jack said.

“How are you?” Brad was another one of the doctors at the hospital.

“Good. Long day?”

“Pretty much.”

Yet outside the quotes were great lines.

That nurse at the hospital that had him hot and bothered finally talked to him. He hoped she’d be at this party tonight.

When it came to my turn for input, I suggested it would be more fun if the men talked about Brad’s love interest.

“Brad, what’s up?” Jack said.

“Long day. You? But, Jane finally talked to me. Said she’s coming tonight. Is she?”

“Dude, you have the hots for Jane? You know she never dates the doctors.”

See, because Brad spoke to Jack about his interest in Jane, the conversation went to a new level. We see Brad has an obstacle.

Drop the bombs and follow the shrapnel.

When we tell the story between the quotes, things are said and decisions are made that impact the story. Often we learn things we never knew about our characters.

In Softly and Tenderly, Book Two of the Songbird Novels I wrote with Sara Evans, one of the characters, June, was married to a perpetual adulterer. She’d finally had enough and left him.

When her husband, Rebel, went to see her, she confronted him. Oh, it was a good, tense scene. For about ten lines. Then . . .

I felt like I was writing in circles. She asked him why he cheated. He said it just got easier and easier. But in truth, he loved his wife.

June pressed him again and he’d answer the same way, “It was easy.”

My goal was to show how sin traps people in ways we don’t anticipate.

But something was missing. I finally asked Rebel, “Why do you cheat on her?”

And he answered. “Because she stole my son.”

GASP! What? The bomb he just dropped blew my story wide open and I followed the shrapnel. I developed a new, until then unknown storyline.

June cheated first and for thirty years, Rebel was never sure if their only son was his. But he always treated him like a true-blue son.

Think about the parts in books you skim. It’s the prose, isn’t it? Dialog is what connects us to the characters.

Granted, there is subtexting — when characters don’t tell the truth to hide a secret.

There are moments when we give the reader a break and use prose to describe a scene or setting.

But overall, let dialog do your heaving lifting and tell the story between the quotes.

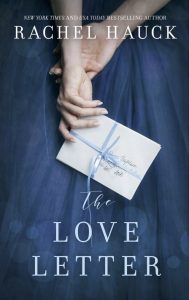

From the New York Times bestselling author of The Wedding Dress comes a story of long-lost love and its redemption in future generations.

Set in stunning upcountry South Carolina, The Love Letter is a beautifully crafted story of the courage it takes to face down fear and chase after love, even in the darkest of times. And just maybe, all these generations later, love can come home in a way not even Hollywood could imagine.

New York Times, USA Today and Wall Street Journal best-selling, award-winning author Rachel Hauck loves a great story. She serves on the Executive Board for American Christian Fiction Writers. She is a past ACFW mentor of the year. A worship leader and Buckeye football fan, Rachel lives in Florida with her husband and ornery cat, Hepzibah. Read more about Rachel at www.rachelhauck.com.